You can contact us 24/7 09330372226

₹0.00

Weight Based Shipping. Kindly Check Weight and Delivery location

The best discounts this week

Every week you can find the best discounts here.

Bairo Adult Chicken Vegetable 10 kg Dog Food

Taiyo Maximum Dog Adult Chicken and Liver 500 gm

Taiyo Maximum Dog Adult Chicken and Liver 20 kg

Pooch Acepron Strip of 10 Tablets for Cats and Dogs

Vetricare Respiratory 100 ml for Dogs

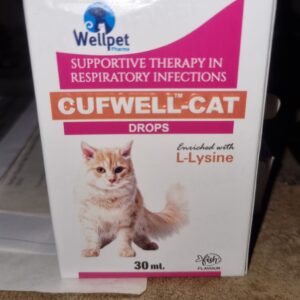

Cufwell Cat Drops 30 ml

₹0.00

Weight Based Shipping. Kindly Check Weight and Delivery location

Why Caution must be exercised in sterilizing male stray dogs of less than 2 years age

Authored by Prasenjit Dutta,

-Retired Civil Engineer,

-Former Secretary and Founder of Pashupati Animal Welfare Society-PAWS at Barasat, Kolkata

-Proprietor of RKD Pet Shop that supplies pet-use products nationwide.

Here is an experience and research based reason why the sterilization of male stray dogs in early life could lead to the dog dying hungry!

Quite commonly noticed effect of sterilizing male stray dogs of less than 2 years age: Subdued Behavior in Young, Sterilized Male Free-Roaming Dogs and Female Dominance at Feeding.

In a nutshell: Even if there is feeder supervision and food assurance, the sterilized young male loses his pecking order and sterilized females in the pack assume male roles of dominance and drives these unfortunate males away when food is served. Finally, if the feeder is not able to prevail over the crisis and modifying the aggressiveness of the females, the male is forced to drift away from the territory and loses his assured food source. What happens to him after that is anyone’s guess. If he doesn’t have an assured feeder, then God help the poor soul in hunting out food and ensuring a grab against un-sterilized competitor dogs male or female. Now let’s read on and see the basis of this concept based on experience.

Introduction:

Young male stray dogs (<2 years) that are sterilized early sometimes exhibit meek, timid behavior and are consistently displaced by sterilized females while foraging. This raises welfare concerns: they might go hungry while females dominate finite food resources. Understanding this requires unraveling how early neutering influences hormonal development, social behavior, and pack dynamics.

1. Hormonal and Behavioral Foundations:

Neutering removes the primary source of testosterone. Behavior clinicians point out that testosterone modulates confidence, territorial assertion, marking, roaming, and dominance behaviors. Neutered males typically show reduced mounting, marking, roaming, and inter-male aggression. This reduction in overt male-typical behaviors can lead to less confidence in competitive situations, such as securing food.

References:

🔗 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7923786/

🔗 https://www.petmd.com/dog/behavior/dogs-neutering-affect-behavior

Additionally, multiple studies indicate that neutered dogs, especially when altered early, exhibit higher levels of fearfulness, anxiety, and emotional instability compared to intact dogs. One review noted that neutered dogs are more prone to anxious or fearful behavior rather than aggression, and changes like increased noise phobia or non-social fear are common.

References:

🔗 https://www.veterinary-practice.com/article/effects-of-neutering-on-undesirable-behaviours-in-dogs

🔗 https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/9/12/1086

In male dogs neutered early in life, the greater is the association with both increased fearfulness and—slight aggression as well.

Reference:

🔗 https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0196284

Thus, hormonal loss plus emotional instability may make young neutered males more submissive—particularly when competing for resources with assertive group members.

2. Developmental Timing Matters:

Neutering a dog before key socialization and hierarchy-forming periods can disrupt their behavioral development. Research by McGreevy et al found that male dogs with minimal lifetime exposure to gonadal hormones (i.e., neutered very early) had higher behavioral risks, including altered social responses and increased fearfulness.

References:

🔗 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5931473/

🔗 https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0196284

3. Free-Roaming Pack Dynamics and Resource Competition:

In stray dog groups, dominance relationships are not strictly sex-based—they hinge on assertiveness, experience, body size, and learned behavior. Resource competition (like that for food) reflects these dynamics. If sterilized females are less hormonally inhibited—or develop compensatory assertiveness or anxiety-driven food motivation—they may more readily compete for and secure food while displacing more timid males.

However, in pet dogs the neutered males are sometimes useful in resource guarding, studies note that neutered dogs overall may show more growling or guarding with humans. In the contrasting case stray dogs and in the pack-foraging context, submissiveness often leads them to withdraw and lose out in food competition.

Reference:

🔗 https://www.veterinary-practice.com/article/effects-of-neutering-on-undesirable-behaviours-in-dogs

Why they are unable to compete with sterilized females is, early spaying in females can occasionally increase aggression or reactivity—making them dominant in fights over food.

References:

🔗 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canine_reproduction

🔗 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6894801/

4. Spatial Behavior and Foraging Patterns:

Castrated male free-roaming dogs often alter their space use and movement patterns—but findings are mixed. Some studies found no change in roaming or home range after sterilization; others suggest subtle shifts in movement or territory marking that may affect confidence or access to established foraging spots.

References:

🔗 https://edepot.wur.nl/629007

🔗 https://swinnercircle.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Research-article-Effects-of-surgical-and-chemical-sterilization-on-the-behavior-of-free-roaming-male-dogs-in-Puerto-Natales-Chile-Garde-et-al.pdf

Young neutered males may lack the territorial marking or patrol behavior that secures feeding areas for older intact dogs. This absence can lead to losing strategic positions to bolder females.

5. Anxiety, Fear, and Feeding Behavior:

Neutering often increases fearful and anxious behaviors. Fear can lead to avoidance of conflicts—an anxious male may yield to females at the food bowl even if physically capable. The emotional cost of defending food may outweigh perceived benefits, particularly among anxious individuals.

References:

🔗 https://www.veterinary-practice.com/article/effects-of-neutering-on-undesirable-behaviours-in-dogs

🔗 https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/9/12/1086

When resource availability is limited—common in urban stray environments—this submissiveness can result in chronic hunger in young neutered males who avoid contesting for food.

6. Management Implications and Recommendations:

a. Delayed Neutering When Feasible:

Experts suggest waiting until after key developmental stages (6–12 months) to reduce risk of submissive behavioral outcomes.

b. Behavior-Supporting Interventions:

Where early neutering is unavoidable (e.g., ABC programs), strategies like multiple feeding points, dispersing food, and minimizing competition should be implemented.

c. Monitoring and Adaptive Feeding Strategies:

Programs should observe group feeding dynamics. If young males are consistently displaced, provide alternative feeding zones.

d. Hormonal Restoration:

Recent studies explored testosterone restoration therapy for neutered males, showing promise in addressing long-term health and behavioral issues.

References:

🔗 https://bmcvetres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12917-025-04869-8

🔗 https://phys.org/news/2025-07-testosterone-health-issues-linked-dog.html

Conclusion:

Sterilisation of young male stray dogs can lead to reduced testosterone-driven confidence, increased fear or anxiety, and social deficits, leaving them vulnerable in food competition. If sterilized females exhibit assertive or food-guarding behaviors, they may dominate feeding hierarchies, causing males to go hungry. Evidence from canine behaviorists and field studies confirms these risks. Humane management should combine sterilisation with behavioral considerations—delaying neutering where possible, adjusting feeding strategies, and monitoring welfare outcomes.